I’m a permanent expat.

I’ve spent half my life — 23 years and counting — outside of my home country, the US. I’ve spent 18 of those years in Taipei, Taiwan, which was named in a survey last year as the eighth most attractive place to live for expats. I spent another five years with my family in Shanghai, China, which snagged the number three spot in the same survey.

Living abroad, whether permanently like me — or for a temporary stint measured in weeks, months, or years — has its share of “perils” (I’ll get to those later).

There are, of course, a number of “pleasures” associated with living the expat life. Enough to make the journey personally and professionally enriching, meaningful, and fun.

If you’ve ever considered taking the plunge and moving to another country for work, study, or just plain fun, here are some things to consider:

The “pleasures” of expat life:

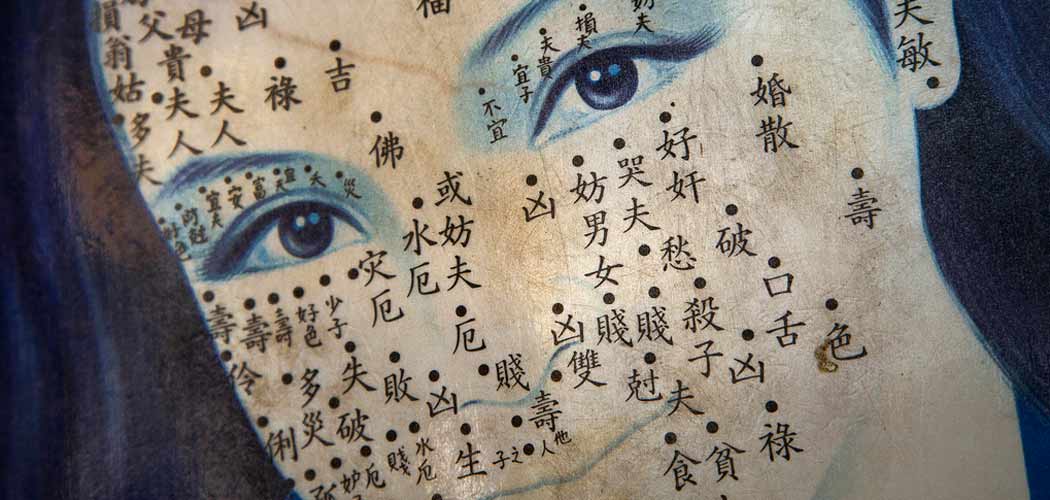

The opportunity to live in a radically different culture steeped in history. In my case, I’m living in a society that is grounded in over 5,000 years of history. One that has used the same written language continuously for well over half that time. And one which has experienced massive social and political disruptions over the past 100-plus years, including several revolutions and wars. Even though I studied the history and language of China for years before even coming out here— and having lived here for nearly a quarter of a century — there’s always something new to learn and enjoy.

The chance to master a foreign language, to the point where it isn’t “foreign” anymore. Chinese is not an easy language to master. But after telling your personal back story for what seems like 10,000 times, negotiating directions with taxi drivers of varying temperaments, and doing the hundreds of other little and big things that make up daily life — in a language you didn’t grow up with — somehow, you just get the hang of it.

The chance to give your children a truly immersive, bilingual educational experience (especially if you’re like me and grew up in a mono-lingual household, except for the occasional word in Slovak or Yiddish).

The opportunity to cultivate a radically fresh perspective on your own culture. Living outside of my home country for so long, I’ve learned what it’s like to be an outsider. Each time I return to the US, I feel out of place, at least for the first few days or weeks that I’m back. I make comparisons. I’m confused by some of the newer cultural signals and icons that have sprung up in my long absence. I suffer, in other words, from what I call “reverse culture shock”. But there’s a flip side to this: while I may feel a little like a foreign tourist in my own land everytime I return home, I also have acquired a much deeper appreciation for my cultural and national heritage.

Access to quality, affordable healthcare. Of course, this depends entirely on the country where you reside. But where I live — Taiwan — the quality of healthcare is very good, and out of pocket costs are very low, especially compared to the US. (This contrasts starkly with the situation in neighboring Mainland China, where I’ve also lived. Outside of a few privately-owned clinics that cater to expats on foreign insurance plans, the quality of the local healthcare system is abysmal).

Room to stretch and grow professionally. In addition to the personal advantages of living overseas for an extended time, there are a number of pluses to working abroad. I’ve often been presented with more opportunities to stretch my wings professionally, to tackle projects and assume responsibilities that I might not have had the chance to take on by working at home, and to meet people I may have never had the chance to meet.

The food! Oh yes, the food! Need I say more? Great stuff. (And for the record, I’ve never — not even once — seen a “fortune cookie” served at a restaurant in either Taiwan or Mainland China. That’s an American invention.)

…And a few of the “perils”

Permanent “otherness”. No matter how well you speak the language or understand the culture, you’ll always be an outsider in a culture that is, well, not your own. In the first few months or even years of expat life, you’ll likely suffer from some degree of “culture shock”. And while the feeling of shock does subside over time, and you may eventually convince yourself that you’ve thoroughly assimilated into your host culture, it’s hard to completely eliminate the feeling that you are, fundamentally, different. Because you are.

Fraying of family bonds. This one is perhaps the toughest of all to deal with. Ever miss a milestone event in your family like a birthday, wedding, or college reunion—or the memorial service of a close friend or loved one? I’m sure you have. But what if it’s the norm? What if, like me, you’re simply unable to shuttle 7,000 miles each time there’s an important event in your family. Or you have to miss most of your family’s holiday gatherings, year after year. Email and Skype are fine, but they are no substitute for a hug or a kiss. (Note: I’m fortunate to have a wonderful wife and children in Taiwan, what I’m referring to here of course is my extended family and friends in the US).

Currency risk. When I returned to Taiwan in 1997 after picking up my MBA back in the US, I once again began earning income in the local currency. In my very first month on the job, the Taiwan dollar depreciated in value — overnight — by over 20%, thanks to the fallout from the Asian financial crisis that swept the region. Since I had taken out tens of thousands of US dollars in student loans, those loans shot up in value. My salary remained the same, but now the cost of my MBA suddenly went up by 20%. Didn’t learn that at Wharton.

Double taxation. As an expat, the taxman knocks on my door not once, but twice. Next week, when the dreaded April 15 deadline arrives, I’ll file my US income taxes with the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). In May, I’ll file again, but this time with the Taiwan tax authority.

Yes, like all expats, I get an exemption up to a certain amount of my income because I live abroad. And yes, I can deduct the tax I pay in Taiwan from the amount I owe the IRS. Nonetheless, every year at this time, I write the IRS a check that I would much rather put into my kids’ college fund. (The US is the only government that taxes its citizens on income earned abroad. I haven’t done the research to find out why and probably won’t bother. All I can say is it isn’t fun.)

The “bamboo ceiling”. Thousands of miles and a dozen time zones away from headquarters, we expats need to rely on email, phone, and videoconferencing to keep us connected. But as we all know, the 24/7 connectivity these technologies provide can never serve as a substitute for in-person meetings and interactions. Long distances often mean we can’t get the mentoring and coaching we sometimes need to grow professionally; to earn the credit we deserve for a project done well; or to build the relationships we need in order to thrive in highly complex, multinational corporate environments. Need to resolve a delicate people issue? Want to be considered as a candidate for more senior positions or new roles that open up in your company? It’s not impossible to do any of these simply because you work in another market, of course. It’s just harder.

Are you an expat? Or are you thinking of taking the plunge and moving yourself and your family to a whole new country and culture? Let me know what you think about the pleasures— and perils — of expat life in the comments below.

Connect with me on Twitter @glennleibowitz

This month, I’ll be launching a new podcast all about writing: Write With Impact. I’ll interview writers of all stripes. I’ll talk to them about who and what inspires them, strategies and techniques they use, and what advice they have for writers like yourself. Click here and be the first to find out when I launch, and while you’re at it, grab a copy of my free ebook with 10 timeless tips (and 10 gorgeous images) for writing with more impact.